This year, I read 40 books, which included 11 novels and 29 non-fiction books. I am currently reading Maoism: A Global History by Julia Lovell, and that will likely be the last book I read for the year.

Looking over the reading list for this past year, I have to admit that there just aren’t that many great books to recommend. Most of the books I read were “award-winners” or highly recommended either on ‘best of’ lists or from friends, so there was already a winnowing selection process happening in the books I chose to read (i.e. I didn’t go to the bookstore and pick up random copies of things). But as I step back a bit this Christmas and look over my reading list, I am unhappily surprised to find just how little impact most of these books made whatsoever, either on my thinking or just as good stories.

I think at the core of it, the challenge is simply that most of these books just failed to live up to expectations. Many of them have ambitious agendas, either as novels and what they are trying to do with their stories, or as non-fiction books trying to change the way we see a subject. And most simply missed the mark. I don’t think there is a deep lesson here, other than to say, I am always open for bold works, and hope to read more of them in the future.

Okay, now here is the list:

First Place: ‘Maoism: A Global History’ by Julia Lovell and ‘Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China’s Last Golden Age’ by Stephen R. Platt

There is some danger in recommending a book like Maoism when you are only about a third of the way through it. That said, this China-related duo is the new canon by which to understand the rise of China and its place in the world today. Both works are fundamentally revisionist, but done in such deep and intense ways that it may take years for us to fully understand their implications.

Maoism takes as its subject the thought and philosophy of Mao, but places it into the international context of the major events of the 1900s. Lovell shows that Maoism was hardly limited to just mainland China, but actively exported as a political ideology by the Chinese Communist Party over the decades across the world, from South America to Africa to Southeast Asia and even to Western Europe. Far from being a political intellectual backwater, Beijing actively underwrote some of the most important events of the Cold War and beyond.

That’s fairly revisionist, since the CCP likes to project an image of China as a humble developing nation with limited ability to use hard or soft power to influence world events. Lovell shows, however, that that image is almost entirely constructed, and not only demonstrates how Maoism has changed the trajectory of the world, but also how and why the CCP was successful in exporting this theory elsewhere.

Meanwhile, Imperial Twilight does for economics what Maoism does for China’s politics. Platt shows how trade, mostly around opium but also other goods, created the foundation for the modern Chinese state. The book is incisive but complicated — it shows not only the horrendous depredations instigated by the West against China, but also how the Chinese people themselves often actively participated in the events that transpired across the Opium Wars.

Platt’s work revises both our understanding of the so-called “century of humiliation,” but also how the current trade war is really a fight that has been going on for centuries, balancing the interests of the West and China over everything from resources, to business and market access, to who controls the world’s waterways and trade routes.

Together, Maoism and Imperial Twilight are the best of an absolute avalanche of new books published on China and its interactions internationally. Can’t recommend them enough.

Second Place: ‘The Plotters’ by Un-Su Kim

This novel is spectacular, and it is sad that it won’t ever get the kind of distribution it deserves in the United States.

It’s a thriller built around assassinations, so in that regard, it is fairly typical in terms of framing. But then Kim goes so far beyond that basic premise to show not only the depths of personalities of the characters in this underworld, but also how their actions and the meaning behind them have and don’t have effects on the world around them.

It’s a book filled with ennui, of psychological drama, of capturing the essence of what it means to be human, of realizing both the power and powerlessness of assassinations as a “career.” In this, Kim fuses all kinds of genres together into a piece that is great literature, that is triller, that is character drama, that is just an all-around incredible book. It’s not going to meet your expectations (whatever they might be), but if you are open to new approaches to well-worn tropes, this is a book that should be at the top of your list.

Third Place: ‘Leadership in War: Essential Lessons from Those Who Made History’ by Andrew Roberts

I hate the self-help genre, and so I don’t have great context on the whole ‘leadership studies’ category. That said, Roberts, who is a lifelong historian focused on the great power figures of history, has brought a synoptic lens to all the leadership and biography studies he has conducted over the years into this taut book on the leadership lessons one can learn from nine of the most influential people in Western history the past few centuries.

It’s ambitious, and certainly may not be everyone’s favorite book (how can you really evaluate Napoleon in 25 pages anyway?) That said, Roberts has done the work to research these figures, and so those 25 pages aren’t superficial, but deeply curated and selected.

Ultimately, the lessons are probably the same as you would get from any book in this genre, but seeing how the personality traits and cultivated skills of these folks directly link to the history they created is an excellent lens for seeing how we do our work. I enjoyed it a lot, and it is a short read to boot.

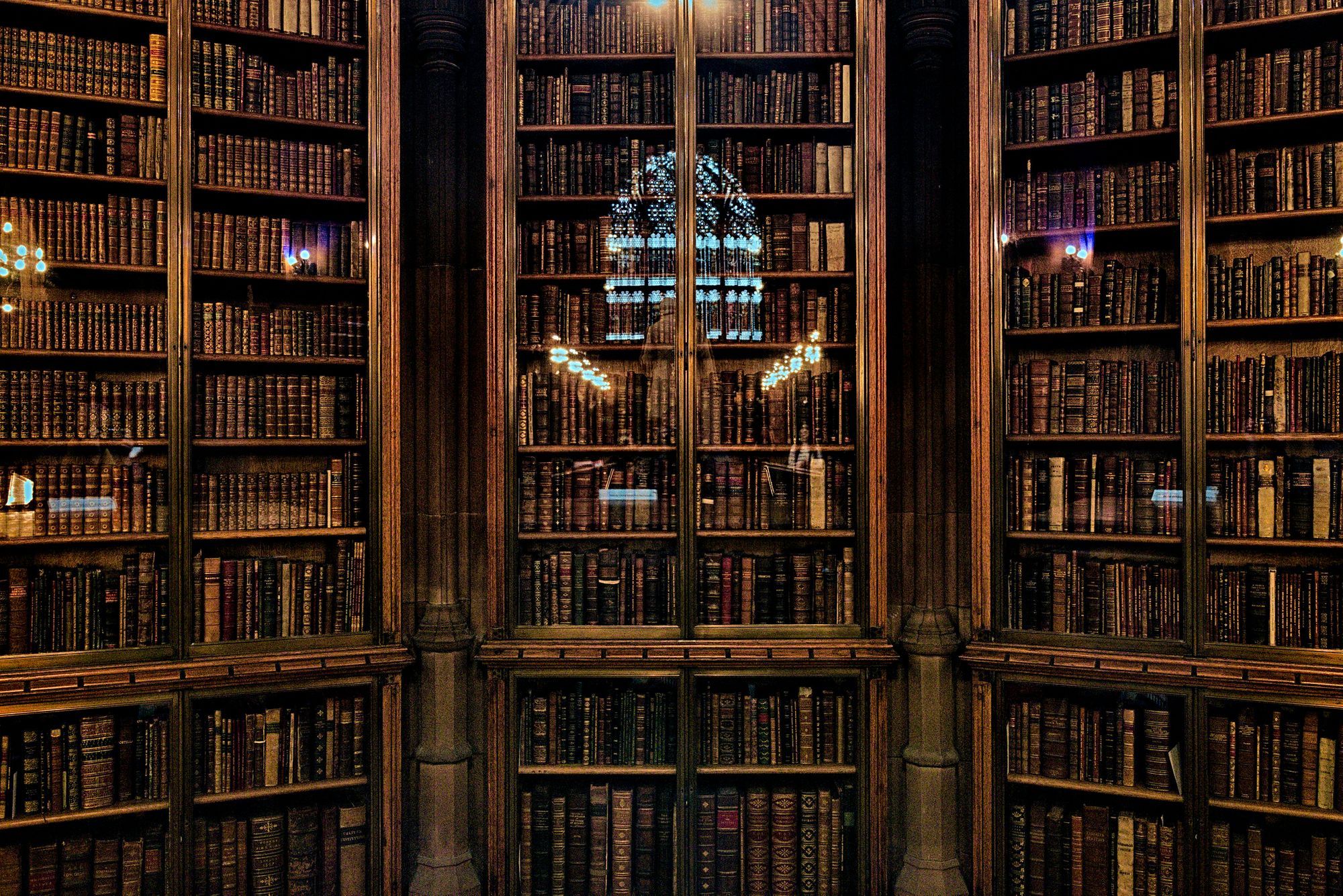

Cover image by Vicente used under Creative Commons